How Cross-Border Payments Work: Settlement, Clearing, and the Correspondent Chain

International wire transfers don’t move money the way most people think. Learn how settlement, clearing, and correspondent banking really work—and why cross-border payments take days, not seconds.

Every year, roughly $195 trillion moves across national borders, per J.P. Morgan and FXC Intelligence estimates. Yet even finance professionals who initiate these payments daily often have only a vague understanding of what happens between clicking send and the beneficiary receiving funds.

That gap is expensive. The World Bank Remittance Prices Worldwide database puts the global average cost of sending remittances at 6.49% as of Q1 2025, with some bank-to-bank corridors exceeding 12 to 15%. The G20's cross-border payments roadmap targets meaningful cost reductions by 2027, but progress is behind schedule across nearly every metric. Explicit fees are only part of the cost. When a $500,000 supplier payment takes five business days instead of one, the real expense is storage charges accumulating at port while the seller or shipping line holds the goods pending payment confirmation, or working capital locked in transit that cannot cover payroll in another subsidiary.

Understanding where value moves, where it waits, and what causes it to wait is the starting point for evaluating any alternative.

Initiation, Clearing, and Settlement

Initiation

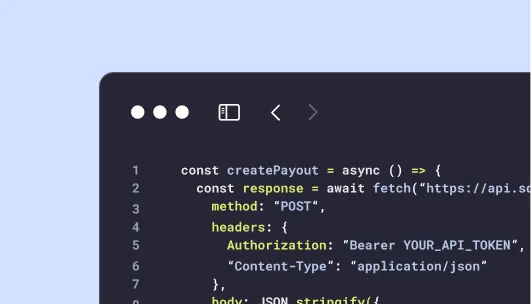

The sender creates a payment instruction through a banking portal, API call, or paper form. At this point, no money has moved. The sender's account has been debited or earmarked, but the beneficiary has received nothing. Payments at this stage are typically reversible because the sending bank has not committed anything to the interbank network. For the sender, this is an important operational detail: if you catch an error in the first few hours, recall is usually possible. Once clearing begins, recall becomes significantly harder and is often impossible.

Clearing

The payment instruction is transmitted, validated, and reconciled between financial institutions. For cross-border payments, this typically involves SWIFT (the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication), which connects over 11,000 institutions across more than 200 countries.

SWIFT handles the messaging. It does not move money. When a bank sends a SWIFT MT103 (a single customer credit transfer message), it creates an obligation between institutions. The acknowledgment (ACK) the sender receives confirms only that the message reached the next bank in the chain. It does not confirm that funds arrived, that compliance screening passed at the receiving bank, or that the beneficiary's account has been credited.

This is where the real delays begin. Every intermediary bank in the chain performs its own sanctions screening, AML checks, and risk assessments independently. The reason is regulatory externality risk: if the beneficiary turns out to be sanctioned and an intermediary bank facilitated the transfer, that intermediary faces enforcement exposure regardless of what the originating bank's screening showed. So each bank screens defensively. One flagged name match at any point in the chain pauses the entire payment until a compliance analyst investigates and clears it.

Settlement

Settlement is the final, irrevocable transfer of value. In the United States, two systems handle this. Most cross-border USD payments clear through CHIPS (the Clearing House Interbank Payments System), which processes roughly $1.8 trillion daily by netting offsetting obligations between banks. In 2024, CHIPS achieved a 29:1 netting efficiency: every $1 of intraday funding supported $29 in settled value. CHIPS then settles its net positions through Fedwire, the Federal Reserve's real-time gross settlement (RTGS) system.

Fedwire also settles payments directly, one at a time, with immediate finality. It processed an average of 836,000 transactions per day in 2024 at roughly $4.51 trillion in daily value, per Federal Reserve data. Time-critical or very large individual cross-border transfers often settle directly over Fedwire rather than waiting for a CHIPS netting cycle. Either way, Fedwire is the ultimate settlement backbone: whether a cross-border payment clears through CHIPS or routes directly, final settlement runs through the Federal Reserve's books. Neither system is cross-border in itself, but both are critical infrastructure for the domestic leg of international wires. If Fedwire is closed, final settlement waits until it reopens, which is why weekend and holiday timing adds days to cross-border payments.

The distinction between clearing and settlement matters more than most people realize. A payment can be "cleared" (the beneficiary's bank has received the SWIFT message and confirmed arrival) but not yet "settled" (the actual reserve account debit at the central bank has not occurred). In a system failure or bank insolvency scenario, an unsettled payment can be reversed. This is why settlement finality, not just message confirmation, is what matters for large-value transactions.

The Correspondent Banking Chain

Domestic payments are straightforward: both banks share a central bank ledger. Cross-border payments are structurally different because a bank in the United States and a bank in Mexico do not share a central bank and may not have any direct relationship. The payment has to travel through intermediary banks, called correspondent banks, that maintain bilateral relationships and pre-funded accounts with each other.

Consider a USD payment from a U.S. manufacturer to a parts supplier in Monterrey, Mexico. The correspondent chain might look like: the sender's bank in Chicago, a New York clearing bank like Citibank or JPMorgan that maintains a direct correspondent relationship with a Mexican bank, and the beneficiary's bank in Monterrey. In a high-volume corridor like U.S.-Mexico, three institutions is typical. In thinner corridors, the chain can stretch to four or five. Each institution in the chain applies its own compliance screening, operates during its own business hours, and processes payments through its own queue. Three institutions, three sets of operating rules, three potential points of delay, and that is the efficient case.

Nostro Accounts and Trapped Capital

Correspondent banks maintain pre-funded accounts with each other, called nostro and vostro accounts, denominated in the relevant currency. These accounts must hold enough balance to cover expected payment flows. If the nostro account does not hold enough of the required currency, the payment queues until the account is replenished, a process that can take hours. As the sender, you have no visibility into this. Your bank shows the payment as sent. The beneficiary sees nothing.

The capital economics of nostro accounts drive the entire correspondent banking structure. Maintaining a pre-funded balance in the correspondent's local currency ties up capital that earns below-market returns. The correspondent absorbs that cost and recovers it through fees. But when payment volumes in a given corridor decline, the risk-adjusted return on that locked capital drops below the bank's internal hurdle rate, and the bank exits the relationship. This is the mechanics behind what the Financial Stability Board has documented as de-risking: a roughly 25% decline in active correspondent banking relationships since 2011, though the rate of decline has slowed since 2018.

De-Risking and Shrinking Corridors

De-risking hits hardest in regions where it matters most. Sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, and parts of Southeast Asia have seen the steepest declines in correspondent access. When a bank exits a corridor, the remaining routes get longer. A payment that previously routed through two correspondents might now require three or four. Each additional hop adds fees (typically $25 to $50 per intermediary), compliance screening time, and FX conversion costs. In less liquid corridors, FX markups can reach 2 to 4% above the interbank rate because each intermediary bank takes a temporary currency position it cannot hedge efficiently.

For a company paying a supplier in a de-risked corridor, the total cost of a $100,000 payment, including explicit fees, FX markups, and opportunity cost of capital in transit for four to five days, can reach 7 to 10% of the payment value. That compounds over hundreds of transactions a year.

Why Payments Take Days

The delay is not caused by any single bottleneck. It is the compound result of several structural factors interacting simultaneously.

Time zones and cut-off times. Banks process payments during local business hours. A payment initiated in New York at 4 PM ET arrives at a London correspondent after their processing cut-off, queuing for the next business day. If initiated on a Friday, the payment does not process until Monday. Layer in local holidays at the beneficiary end, and a single payment can lose two or three calendar days to scheduling alone.

Duplicative compliance screening. This is the single highest-cost structural inefficiency in cross-border payments. If originating banks' sanctions and AML screening were accepted by downstream correspondents, most payments could clear in hours. But regulatory externality risk makes this impossible: each intermediary faces its own enforcement exposure, so each one screens independently. There is no shared compliance infrastructure across the correspondent chain, and no legal safe harbor for relying on another institution's screening. Until that changes, this will remain the primary driver of delay.

Nostro liquidity gaps. When a correspondent's nostro account is short of the required currency, the payment queues. Replenishment depends on the correspondent's own funding cycle, which may not align with the payment's urgency. For the sender, this delay is invisible and uncontrollable.

Batch processing windows. CHIPS nets payments in cycles rather than settling each one individually. The 29:1 netting ratio saves enormous amounts of liquidity, but a payment arriving just after a netting cycle closes waits for the next one. Fedwire settles in real time but has its own operating hours (the Fedwire Funds Service runs weekdays, roughly 9 PM ET to 7 PM ET the following day).

A common question: does the Federal Reserve's FedNow Service, launched in 2023, change any of this? FedNow enables instant, 24/7 settlement between U.S. banks, but it does not currently serve a role in cross-border flows. CHIPS and Fedwire handle the domestic settlement leg of international wires; FedNow is designed for retail and consumer payments and does not connect to foreign central banks, handle FX conversion, or replace any part of the correspondent chain. A payment from the United States to Mexico still requires intermediaries, compliance screening, and currency conversion regardless of how fast the domestic legs settle on either end. Efforts like the BIS's Project Nexus aim to link domestic instant payment systems across borders, but these are early-stage and would still require the compliance and FX infrastructure that drives today's delays.

SWIFT's Global Payments Innovation (GPI) initiative has improved tracking and speed for direct routes: SWIFT reports that 75% of GPI payments reach the beneficiary bank within 10 minutes. But GPI works best for direct two-bank routes. For multi-hop payments through de-risked corridors, where speed matters most, GPI provides limited benefit because the delay occurs at each intermediary, not on the messaging network.

Where Stablecoin Settlement Fits

The structural cost of correspondent banking is the chain itself: each intermediary adds time, fees, compliance screening, and a potential failure point. Stablecoin-based settlement compresses the cross-border leg by replacing that chain with a different mechanism.

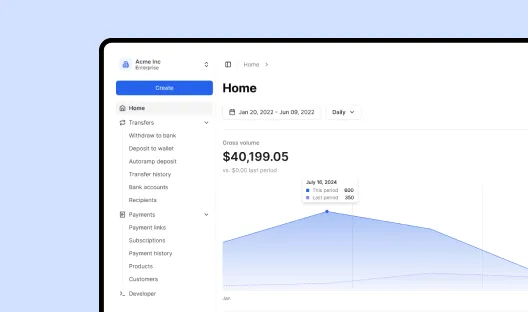

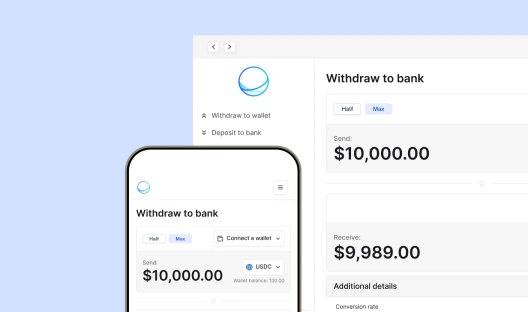

In this model, fiat currency converts to a stablecoin at a licensed on-ramp in the sending country, transfers on a blockchain network (operating 24/7 with settlement finality in seconds to minutes depending on the network), and converts back to local fiat at a licensed off-ramp in the receiving country. The sender and beneficiary only touch fiat. The stablecoin layer is infrastructure between the two conversion points.

Take the earlier Mexico example. Instead of routing through the correspondent chain over three to five days, the U.S. manufacturer sends USD to a payment provider that converts it to USDC at a licensed on-ramp, the USDC transfers on-chain, and a licensed off-ramp provider in Mexico converts USDC to MXN and deposits pesos to the supplier's account. The sender and the supplier both interact only with fiat. Mexico's Fintech Law (Ley Fintech) provides the broader fintech licensing framework under which providers like Bitso operate as CNBV-authorized payment institutions with connections to Mexico's SPEI real-time settlement system. In practice, this infrastructure handles stablecoin-to-MXN conversion at meaningful volume, though the Fintech Law's virtual asset provisions do not specifically contemplate stablecoins (which are excluded from the law's virtual asset definition because they are pegged to fiat). The on/off-ramp infrastructure works within existing fintech authorizations rather than under a stablecoin-specific framework.

The correspondent chain is replaced, but intermediaries are not eliminated. The on-ramp provider, the blockchain network, and the off-ramp provider are all third parties in the payment flow. What changes is the nature of the intermediation: instead of a chain of banks each holding pre-funded balances and screening independently over days, the conversion happens at two endpoints with on-chain transfer in between. For an onboarded customer with funds already at the provider, end-to-end settlement can complete in minutes. Where the fiat legs involve bank transfers (ACH on the U.S. side, SPEI on the Mexico side), the total time depends on those systems as well. The correspondent nostro requirement is restructured rather than eliminated: the on-ramp provider needs USD liquidity and the off-ramp provider needs MXN liquidity. If the off-ramp runs low on pesos, the conversion slows or the spread widens, which is functionally similar to a nostro gap in the correspondent model. The capital is structured differently, and the intermediary chain is shorter, but liquidity risk has not disappeared.

What the Numbers Show

On-chain stablecoin transfer volume reached roughly $27.6 trillion in 2024, per Chainalysis. That figure is gross on-chain volume and includes automated bot trading, DEX activity, treasury movements, and other flows that are not commercial cross-border payments. The actual volume of B2B payments settling through stablecoin on/off-ramps is a small fraction of that total, though growing. J.P. Morgan's Kinexys platform has surpassed $1.5 trillion in notional value of tokenized interbank transactions, but these are institutional flows between bank entities on a permissioned network, not SMB supplier payments on public blockchains. The distinction matters for evaluating where stablecoin rails are production-grade versus early-stage.

What Stablecoin Settlement Does Not Eliminate

Compliance obligations do not disappear. AML/KYC requirements apply at the on-ramp and off-ramp. Sanctions screening is mandatory. The Travel Rule requires originator and beneficiary information for qualifying transfers in every major jurisdiction. The technology changes the plumbing between the compliance checkpoints, not the checkpoints themselves.

Stablecoins also carry their own risk profile. Reserve risk is the most concrete. In March 2023, USDC briefly depegged to $0.87 after Circle disclosed $3.3 billion in reserves held at Silicon Valley Bank. Had those deposits been fully unrecoverable, USDC would have faced a roughly 8% reserve shortfall across its then-$40 billion circulation. Circle has since restructured its reserves (the majority now held in short-dated Treasuries and repos through the BlackRock-managed Circle Reserve Fund). Regulatory frameworks are also tightening reserve standards: the EU's MiCA requires significant reserves held in European banks, and the GENIUS Act (signed into law in July 2025) establishes federal reserve composition requirements for payment stablecoin issuers in the United States, with implementing regulations still being finalized by the OCC, FDIC, and Federal Reserve. But reserve transparency and custodian diversification remain active areas of risk management, not solved problems.

Evaluating Corridors: A Framework

The question is not whether stablecoin settlement is "better" than correspondent banking. It is which approach fits a given corridor, and answering that requires evaluating three things in order: the regulatory status of stablecoin infrastructure in both markets, the availability and liquidity of licensed on/off-ramp providers, and the all-in cost of the current payment method (not the headline wire fee, but fees plus FX spread plus capital opportunity cost). Most evaluations skip the first question and jump to speed. That is a mistake.

Three corridors illustrate how the framework applies in practice.

U.S. to Mexico: The Established Case

Mexico's Fintech Law (Ley Fintech) created a licensing framework for fintech institutions, including those that handle virtual assets, under CNBV and Banco de Mexico oversight. Providers like Bitso operate as CNBV-authorized electronic payment institutions with established MXN liquidity and SPEI connectivity. On the U.S. side, the sender's provider holds state money transmitter licenses and operates under FinCEN registration.

One nuance: the Fintech Law's virtual asset definition excludes stablecoins (because they are pegged to fiat), so on/off-ramp operations function within the broader fintech licensing framework rather than a stablecoin-specific regime. Banco de Mexico has signaled cautious oversight, and Mexico is actively consulting on dedicated stablecoin rules, which suggests the current approach is recognized as provisional. That said, this is one of the most operationally mature corridors for stablecoin-based settlement. The infrastructure exists, providers are licensed and supervised, and the rails are production-grade even as the stablecoin-specific regulatory layer continues to take shape.

The operational result: a payment that takes three to five days through the correspondent chain and costs 3 to 4% all-in (wire fee plus FX markup plus capital cost) can settle in minutes at a fraction of that cost.

The U.S.-to-Philippines corridor has a similar infrastructure profile. The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) VASP framework licenses providers like Coins.ph, which integrate stablecoin-to-peso conversion with the Philippine payment systems InstaPay and PESONet. The BSP has taken a more cautious posture than Mexico's CNBV, including a freeze on new VASP license approvals, but existing licensed providers operate with clear regulatory backing. These are corridors where the infrastructure is operational and supervised, even if the regulatory frameworks were not originally designed with stablecoin payment flows as the primary use case.

U.S. to Nigeria: The Transitional Case

Nigeria is building one of the more comprehensive digital asset regulatory frameworks in sub-Saharan Africa, though the gap between legislative progress and operational readiness remains significant. The Central Bank of Nigeria issued guidelines in December 2023 allowing banks to open accounts for licensed crypto service providers, reversing a February 2021 directive that had prohibited banks from servicing crypto firms entirely. The Investments and Securities Act 2025, which took effect in March 2025, placed digital assets under SEC Nigeria oversight with explicit licensing requirements for exchanges, custodians, and wallet providers. This is substantive legislation.

The challenge is implementation speed. Nigerian banks remain cautious about servicing crypto firms, in part because the CBN's posture shifted sharply between the 2021 prohibition and the 2023 opening, and institutions are waiting to see whether the current approach holds. The SEC's licensing program (the Accelerated Regulatory Incubation Programme) has approved only two providers as of early 2026, and banks will generally only service firms with SEC authorization. The coordination between CBN banking oversight and SEC trading oversight is developing, with joint technical committees established in late 2024, but market participants describe it as a work in progress.

For a U.S. company evaluating this corridor, the question is not just "is it legal?" It is "can my provider reliably convert stablecoins to naira through a licensed off-ramp that maintains consistent banking relationships?" Licensed providers have regulatory protections that unlicensed ones do not, but even licensed firms have faced operational disruptions as banks calibrate their risk appetite. The stablecoin infrastructure may be faster and cheaper than the correspondent alternative, but the operational risk at the last mile is higher than in Mexico or the Philippines at this stage, and that risk has to be priced into the evaluation.

De-Risked Corridors: Where Alternatives Are Shrinking

Parts of sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Islands present a different calculus. These are markets where correspondent banking relationships have withdrawn and continue to withdraw. The FSB's 25% average decline understates the impact in specific corridors where the withdrawal has been steeper.

In these markets, stablecoin rails may be the most viable path to maintaining reliable payment access. But the evaluation must be clear-eyed: off-ramp liquidity is often thin, local regulatory frameworks may be underdeveloped, and the fiat conversion step carries its own compliance and operational risk. A stablecoin payment that settles on-chain in two minutes but takes three days to convert to local currency at the off-ramp has not actually solved the speed problem. The benefit of stablecoin rails in de-risked corridors is real, but so are the constraints, and the analysis has to account for both.

The same framework applies everywhere. For institutional treasury movements between major financial centers (New York to London, Singapore to Tokyo), the existing correspondent infrastructure works well enough that introducing a new settlement mechanism may not justify the overhead. The point is not that one approach is universally better. Every corridor has a different regulatory, operational, and cost profile, and the evaluation has to start there.

The Bottom Line

Cross-border payments are slow and expensive because the structure is complex: multiple sovereign jurisdictions, independent compliance regimes, and a chain of intermediary banks each adding their own friction. Understanding that structure is the prerequisite for evaluating any alternative.

The pace of stablecoin regulation accelerated sharply between 2024 and 2025. MiCA is fully operational in the EU. The GENIUS Act is now law in the United States, with implementing regulations in development. Markets like Mexico, the Philippines, Singapore, and the UAE have fintech and virtual asset licensing frameworks under which stablecoin providers operate, though the specificity of stablecoin-focused regulation varies. Others, like Brazil and Nigeria, are in earlier stages of building their frameworks.

For any business that moves money across borders, the practical next step is to audit your highest-cost and highest-volume corridors against the framework in this article. For each one, document the all-in cost of your current payment method (not the wire fee, but fees plus FX spread plus the opportunity cost of capital in transit), identify whether licensed on/off-ramp infrastructure exists in both markets, and assess the regulatory ground underneath it. The corridors where the gap between current cost and available alternatives is widest are where the evaluation starts.