The Stablecoin Sandwich: How Modern Cross-Border Payments Actually Move

The “stablecoin sandwich” is the architecture behind faster cross-border B2B payments: fiat in, stablecoin transfer, fiat out. Learn how it works, why it matters, and what compliance looks like at every layer.

There’s a payment architecture quietly processing billions of dollars in cross-border transactions, and it has an unexpectedly casual name: the stablecoin sandwich.

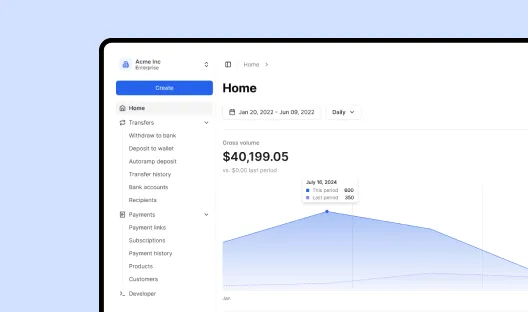

The name describes the structure. A cross-border payment enters the system as fiat currency, moves across borders as a stablecoin, and exits as fiat currency on the other side. Fiat on both ends, stablecoin in the middle. The sender deposits dollars. The beneficiary receives local currency. In between, the payment settles on a blockchain network in minutes rather than routing through a multi-day correspondent banking chain.

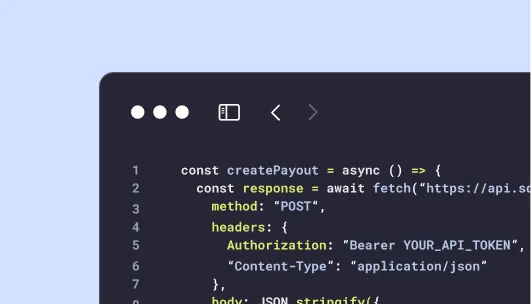

If you're evaluating cross-border payment infrastructure (whether you're a fintech building payment products, an enterprise treasury team optimizing working capital, or a compliance officer assessing new settlement models), understanding this architecture is increasingly essential. Here’s how it works, why it’s gaining traction, and what responsible implementation looks like.

The Architecture: What Happens at Each Layer

The stablecoin sandwich has five distinct steps. Each involves different participants, different risk profiles, and different compliance obligations.

Step 1: Fiat Deposit (The First Slice of Bread)

The sender initiates a payment in their local fiat currency, typically by depositing funds via wire transfer, ACH, or direct bank debit into an account held by the payment provider. At this stage, the transaction looks identical to any traditional payment initiation. KYC verification of the sender has already been completed. The payment instruction specifies the beneficiary, the amount, and the destination currency.

No stablecoins are involved yet. No blockchain interaction has occurred. The sender’s experience is indistinguishable from initiating a conventional wire transfer.

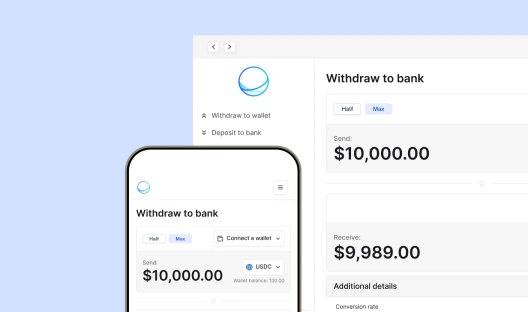

Step 2: On-Ramp Conversion (Fiat to Stablecoin)

The deposited fiat is converted to a stablecoin, typically USDC or USDT. The conversion happens through a licensed on-ramp provider. This conversion is the first point where the payment touches blockchain infrastructure.

The on-ramp provider is a regulated entity: licensed as a money services business, money transmitter, or equivalent in their jurisdiction. They are responsible for ensuring that the fiat-to-stablecoin conversion complies with all applicable anti-money laundering (AML), know-your-customer (KYC), and sanctions screening requirements.

This step is where compliance rigor matters most on the sending side. The on-ramp provider must verify that the sender is a known, verified customer; that the transaction doesn’t involve sanctioned parties or jurisdictions; and that the payment doesn’t exhibit patterns consistent with money laundering or terrorist financing. Sanctions screening at this stage typically checks against OFAC’s Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) list, the UN Consolidated List, the EU Consolidated List, and other relevant sanction regimes.

Step 3: Stablecoin Transfer (The Filling)

This is the cross-border settlement layer, the part that replaces the correspondent banking chain.

The stablecoin is transferred from the on-ramp provider’s wallet to the off-ramp provider’s wallet on a blockchain network. Depending on the provider and the transaction characteristics, this might occur on Solana, Ethereum, Polygon, Tron, or another supported network. The choice of network can depend on factors like transaction fees, network congestion, settlement speed, and the specific corridor.

Settlement on blockchain networks is typically fast: Solana transactions can finalize in under a second, Ethereum in 12 to 15 seconds. This is the step that compresses what was a multi-day process into minutes. The transfer operates 24/7/365. No business hours, no cut-off times, no weekend delays.

An important nuance: blockchain settlement provides what’s often called “probabilistic finality.” After a sufficient number of network confirmations, reversing the transaction becomes computationally infeasible. This is different from the legal finality provided by central bank settlement systems like Fedwire, where a transfer is irrevocable as a matter of law. Both forms of finality are effective in practice, but they derive their security from different sources—one from mathematics and computational cost, the other from legal authority.

Step 4: Off-Ramp Conversion (Stablecoin to Fiat)

The off-ramp provider in the destination country receives the stablecoin and converts it to local fiat currency. Like the on-ramp, the off-ramp provider is a regulated entity with its own licensing, compliance, and AML obligations.

At this stage, the off-ramp provider performs its own compliance checks: verifying the beneficiary, screening against local sanctions lists, and ensuring the transaction meets local regulatory requirements. If the destination jurisdiction has Travel Rule obligations (as most major jurisdictions do), originator and beneficiary information is shared between the on-ramp and off-ramp providers using protocols like TRISA, Notabene, or similar compliance messaging systems.

The off-ramp provider then initiates a local fiat payment to the beneficiary's bank account using domestic payment rails (whether that's a local wire, ACH equivalent, real-time payment system, or mobile money network, depending on the destination country).

Step 5: Fiat Delivery (The Second Slice of Bread)

The beneficiary receives local fiat currency in their bank account. From their perspective, a payment arrived faster than a traditional wire, and in their local currency. They didn’t interact with stablecoins, blockchain networks, or crypto wallets. They received a payment.

This is a critical design point of the stablecoin sandwich: the end users on both sides of the transaction interact only with fiat currency in the traditional banking system. The stablecoin layer is invisible infrastructure.

Why This Architecture Matters for Cross-Border Payments

The stablecoin sandwich addresses specific structural problems in traditional cross-border payments. Understanding why it’s gaining adoption requires understanding what it changes.

It compresses the intermediary chain. A traditional cross-border payment might route through four or more institutions (sending bank, one or more correspondents, receiving bank), each adding time and fees. The stablecoin sandwich reduces this to three participants: the sender’s payment provider (with on-ramp), the blockchain network, and the beneficiary’s payment provider (with off-ramp). Fewer intermediaries means fewer processing queues, fewer compliance holds, and fewer points of failure.

It eliminates dependence on business hours. Correspondent banks process payments during their local business hours. A payment initiated on Friday afternoon in New York may not arrive in Lagos until the following Tuesday or Wednesday, depending on time zones, holidays, and cut-off times. Blockchain networks don’t have business hours. The cross-border leg of the stablecoin sandwich operates continuously.

It can reduce pre-funding requirements. Traditional correspondent banking requires pre-funded nostro accounts in multiple currencies across multiple jurisdictions. This locks up significant working capital. In the stablecoin sandwich model, conversion happens on-demand rather than from pre-positioned reserves, which can free working capital for other uses.

It creates an audit trail. Every stablecoin transfer is recorded on a blockchain with a timestamp, transaction hash, and wallet addresses. This provides a verifiable, tamper-resistant audit trail that can supplement traditional compliance records.

Compliance at Every Layer

One of the most common misconceptions about stablecoin-based payment models is that they somehow bypass compliance requirements. The opposite is true in any well-designed implementation. The stablecoin sandwich doesn't reduce compliance obligations. It changes where and how they're applied.

At the on-ramp: Full KYC verification, sanctions screening against all major regimes (OFAC, UN, EU, UK OFSI), AML transaction monitoring, and source-of-funds verification where required.

During transfer: Travel Rule compliance requires sharing originator and beneficiary information between providers when thresholds are met. These thresholds vary by jurisdiction: $3,000 in the United States, €0 in the European Union (meaning all crypto transfers require Travel Rule data), AED 3,500 (~$950) in the UAE, and SGD 1,500 (~$1,100) in Singapore.

At the off-ramp: Independent KYC verification of the beneficiary, local sanctions screening, suspicious activity monitoring, and compliance with local regulatory requirements.

The compliance architecture in a well-implemented stablecoin sandwich is arguably more rigorous than in traditional correspondent banking, where compliance responsibility is distributed across a chain of intermediaries with varying standards. In the stablecoin model, the on-ramp and off-ramp providers have direct responsibility and clear accountability.

That said, the model’s compliance integrity depends entirely on the quality of the providers involved. An on-ramp or off-ramp with weak KYC, cursory sanctions screening, or inadequate transaction monitoring undermines the entire architecture. When evaluating stablecoin payment providers, their licensing status, regulatory track record, and the specifics of their compliance program matter at least as much as their technology.

Limitations and Considerations

The stablecoin sandwich isn’t a universal solution, and honest evaluation requires acknowledging its limitations.

Fiat endpoints still depend on traditional banking. The first and last miles of the stablecoin sandwich (depositing fiat and delivering fiat) still rely on traditional banking rails. If local banking infrastructure is slow or unreliable, the overall end-to-end experience is constrained regardless of how fast the stablecoin settlement layer is.

Stablecoin risk is real. During the minutes that value exists as a stablecoin in transit, it’s exposed to stablecoin-specific risks: potential depeg events, smart contract vulnerabilities, and blockchain network issues. Well-designed implementations minimize this exposure by keeping stablecoin holding periods as short as possible (typically minutes, not hours or days) and by supporting multiple stablecoins so that exposure to any single issuer is limited.

Regulatory frameworks are still evolving. While MiCA, the GENIUS Act, and other frameworks are creating clearer rules, the regulatory landscape for stablecoin-based payments is not yet fully settled in every jurisdiction. Businesses operating across multiple jurisdictions need to track regulatory developments in each market.

Not all corridors are equally served. The availability and quality of on-ramp and off-ramp providers varies significantly by country and currency. Major corridors (US-Europe, US-LatAm) tend to be well-served. More exotic corridors may have limited off-ramp options or higher costs, particularly for local currency delivery.

Counterparty due diligence is essential. Because the model relies on on-ramp and off-ramp providers, the creditworthiness, licensing status, and operational reliability of these providers are critical risk factors. This is counterparty risk by another name, and it requires the same rigor you’d apply to evaluating any financial intermediary.

The Bottom Line

The stablecoin sandwich is a production payment architecture processing billions in cross-border volume through regulated providers, with compliance infrastructure at every layer.

Its adoption is driven by a straightforward value proposition: for cross-border B2B payments, routing the international leg through stablecoin settlement rails can be significantly faster, more transparent, and less expensive than routing through traditional correspondent banking chains while maintaining (and in some implementations strengthening) compliance standards.

Whether this architecture is right for a specific business depends on the corridors served, the compliance requirements, the provider’s regulatory standing, and the risk tolerance of the organization. But understanding how it works is no longer optional for anyone involved in cross-border payments. The stablecoin sandwich is already here. The question is how quickly your competitors figure that out.